December 22, 2012: Delhi or Splash

I sat in one of the last remaining chairs near the gate and dropped my backpack in front of me. It thumped onto the carpet. I stacked my duffel on top of it, slumped back into my chair, and rested my feet on the duffel. Relaxing. The blue screen overhead asserted that my flight to Delhi was on time, but I was not inclined to believe it. Only twenty-five minutes remained until the scheduled departure time and we weren’t boarding yet. I blew my nose. I was learning that on-time departures are not the United way—of the three United flights I’d had scheduled over the preceding two days, one had been cancelled, one had been delayed, and I’d had to miss the other because of delays elsewhere. It appeared that I would be relaxing awhile longer.

I looked around. The whole Newark airport had seemed crowded, but this end of the concourse was especially so. People clustered around the entrance to the boarding line, waiting for the first boarding call. Not a line, just a crowd of folks standing beside the retractable belt-ropes. This was not nearly as intense, I warbed myself, as the crowds in India. But it was a crowd of Indians. People traveling to spend Christmas with family, most likely.

The young woman next to me had set her rolling bag in front of her and was resting her boots on top of it. Three-buckle brown boots with a moccasin toe, kind of a stylized version of upland bird hunting boots. Like what J. Crew would sell if they marketed footwear for bird hunting.

“Kind of like having a portable ottoman,” I said, gesturing toward her rolling bag, having searched for something better to say and come up empty.

“Yes it is,” she said.

“Nice after a long day on your feet,” I said.

She agreed. Her name was Puntab and she was traveling home for the holidays. She was from a smaller city in southern India. I told her that a buddy of mine was around Bangalore seeing his family, and that he and I would meet in a day or so in Jaipur to do a volunteer vacation. Her town wasn’t too far from Bangalore, she said. She tried to tell me where but I wasn’t getting it. I handed her my iPhone so she could type the city name and pull up a map.

“So you’re doing a . . . volunteer vacation?” she asked as she typed.

“Yes, in Jaipur.”

“What are you doing?”

“I’m not too sure,” I said. “It has something to do with slums and children. Slum children. Apparently there’s a shelter there where the kids can have food and a place to stay, but it’s not in good repair. So I think we’re going to be fixing it. Something like that.”

“Like Habitat for Humanity?”

“Yeah, basically. I think. But the thing is, the needs of the program we’re a part of change all the time, so the program changes week to week. One week it might be construction, and the next it might be handing out food, and the next it might involve medical supplies . . . you just don’t know. I booked this trip two months ago, so it could’ve changed. But I think it’s construction. I hope so; I know something about that.”

She looked at me. “So how does it work with the airfare? Does the program cover it?”

“No I have to pay for that.“

“So why . . . ?” she was starting to smile.

“I know, it’s a long way to go to volunteer.”

“So why not just give the money to the program and let them use it?”

The blue screen above admitted that the flight would be delayed. I had to blow my nose again. It was, I reflected, a reasonable question.

* * *

This trip was supposed to start yesterday. I was jouncing along in a bus that would take me to the train that would take me to the Atlanta airport when I got an email from United announcing that it had cancelled my flight to Newark. That was a problem, since my itinerary called for Atlanta->Newark->Delhi and it was too late in the day to walk to Newark. The email informed me that I would now be departing on the following day, traveling Atlanta->Cleveland->Newark->Delhi. I did not want that delay. But I kept cool. When the bus stopped, I walked to a Burger King, found a seat behind a window (which happened to contain a very large sticker advertising curly fries), opened up my computer, and got on the phone with United. There I remained for fifty-six minutes, waiting on hold, smelling curly fries, searching Travelocity, listening to an irritable lady yell over the intercom what order numbers were ready, and occasionally listening to someone in the Philippines read United’s disgruntled-customer script into the phone. Fifty-six minutes, if you have never tried it, is a long time to smell curly fries and not eat any, particularly if you have skipped breakfast and do not have any pleasant tasks at hand to distract you. But I was determined to eat healthy since I needed to get over my cold. The image of luscious, anaconda-sized curly fries in the window in front of me did not help. After much wrangling, the woman in the Phillipines offered me a flight later that day going from Atlanta->Charlotte->Munich->Frankfurt->Delhi. I said I’d take it. Then she took it back. She said the best I could, after all, do was wait a day as United had originally announced. I changed tacks and tried again. Nothing. Finally I boarded a bus home, leaving without curly fries or a new flight.

my Burger King office

No matter. I used the day to tie up a few loose ends in Atlanta, watch a good movie, and get healthier. Today my girlfriend Anne drove me to the airport where, after trying unsuccessfully to convince her that she should really see India and could probably fit in an overhead compartment, and giving her more kisses in public than she’s really comfortable with, I strode into the terminal refreshed. The blue screens said my flight to Cleveland was on time. I ran through the legs of my trip in my head. I realized that I needed a hard-copy, printed voucher to get in the cab from Delhi to Jaipur. Although I’d printed the voucher for yesterday’s trip, I had forgotten to print the updated one for today’s trip. No problem—I had the email containing the voucher, and surely someone at the airport could print it for me.

The kind United representative at gate D8A said she could help. She gave me an email address to which I could forward the voucher. So I pulled up my email account to forward the voucher and there, like a mine waiting to be stepped on, was another email from United. I opened it. My flight from ClevelandàNewark was delayed, it said. I would not catch the flight from NewarkàDelhi.

“Did you forward that email yet?” Anna asked me. Customers were beginning to line up.

“Now I’ve got another problem,” I said. I showed her the new email.

May the sun eternally shine on people like Anna. She could have told me I was out of luck, or to visit United’s customer service, or to call the Phillipines again and I doubt she would have faced any personal repercussion. I would have probably faced another day’s delay. But she started digging on her computer. She tried to book me on a later United flight from AtlantaàNewark (one that Travelocity showed as full), but that flight was also delayed. In the end she found a Delta flight that would get me to Newark on time, and she booked me on it.

“But the thing about Delta,” she said, “is if you’re not at the gate right on time, they’re gone.” She handed me a boarding pass. I was gone.

Once Delta had delivered me to Newark, I returned to the task of getting my voucher printed. I thought it would be easy. It wasn’t. I tried airline lounges, computer stores, currency-exchanges, and a duty-free shop. I tried Concourse A, the main terminal, and Concourse C. Folks either did not have a printer, did not have access to email, or did not give a damn. I kept roaming. Finally, on the seventh try, a kind woman in an airline lounge that I wasn’t supposed to enter printed the voucher from her personal email account. And so, voucher in duffel, I walked to the end of the concourse, set my luggage on the carpet, and sat beside Puntab with my feet propped up.

* * *

My traveling mishaps are, of course, first-world problems. I look forward to the Jaipur slums. Replace “my flight was delayed” with “I have no home;” replace “I am getting over a cold” with “I have no access to any medical care;” replace “I prefer not to eat curly fries” with “I need food.” The problems of the desperately poor are immediate and significant and addressing them gives one a sense of relevance—a sense of addressing something that matters. These are basic, honest problems far removed from the nitshit problems described above.

I look forward to the Jaipur slums. There is something quintessentially American about leaving behind the patterned nitshit of settled life and traveling to where circumstances are uncertain. Virtually all modern Americans’ ancestors did just that. The iconography of this gamble pervades Americana: it is Plymouth Rock, Ellis Island, Conestoga wagons emblazoned “California or bust,” Chinese immigrants wielding sledgehammers and railroad spikes, Latin Americans waiting outside Home Depot.

* * *

“Well that’s not really the choice,” I told Puntab. “I guess I’m not that unselfish. I was going to go somewhere. It was a question of whether I took my backpack and wandered around in Central America or went to volunteer someplace.”

Puntab nodded.

“I know the airfare is worth more than five days of my work,” I said, “but I guess I’m hoping to get something out of it too.” I fingered my boarding pass and wondered what lay ahead for me. “I look forward to the Jaipur slums.”

United called my boarding zone. I took my phone from Puntab, wished her happy holidays, and joined the cluster near the retractable belt-ropes for our flight across the Atlantic.

Delhi or splash.

December 23, 2012: Fog Fighters

I eyed the passport-checkers carefully. Officials in Atlanta and Newark had warned me that the smattering of mildew spots on my passport could create problems at immigration. I didn’t know when or how the spots had appeared, and they seemed insignificant to me, but having crossed the Atlantic, Europe, and some of Asia to arrive in Delhi, this was not the time to take chances. Immigration was, I told myself, the last hurdle between me and Jaipur. Once through, I had only to use my cab voucher and sit for the four-hour car ride from Delhi to Jaipur. I chose my agent carefully and walked up.

As it turned out, immigration was a breeze. The cab ride was a different story.

I’ll tell it briefly. The voucher promised that I’d receive an SMS—i.e., a text message—telling me how to meet up with the driver. It never came. When I called the phone number listed on the voucher, I could not communicate with the guy who answered. He hung up on me. I called back and passed the phone to Gus, a passenger from my flight who had been born in southern India but lived in Detroit. But Gus spoke a different dialect from the guy at the other end of the phone and they couldn’t communicate. The guy hung up again. I found another native-born traveler—this guy had lived in Atlanta—and he called back on my behalf. After several phone calls back and forth, the guy at the other end agreed to send a cab to the airport and promised that it would be there in fifteen minutes or so. He gave us a phone number for the driver, but the driver didn’t answer when we called. So I stood at the curb with Gus, who had time to kill between flights, in the chill dark and gathering fog.

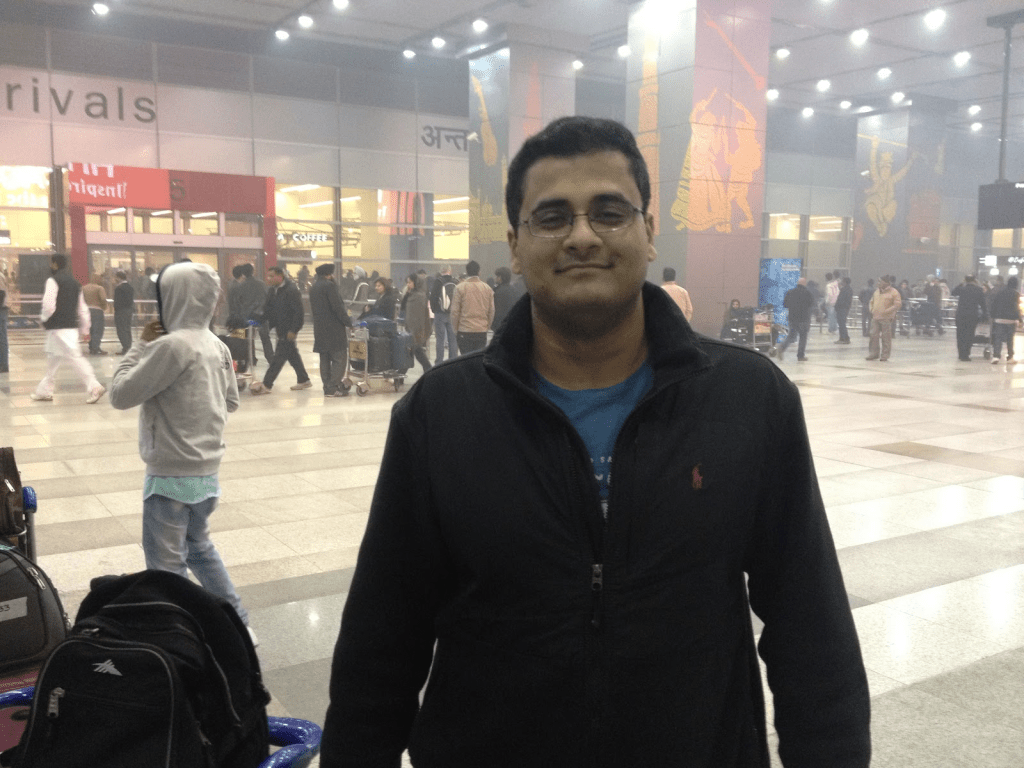

Gus

Just when I was about to give up, a man in a down jacket walked up to us. He glanced around, then looked at me. “Jaipur?” he asked. I hugged him. I bade goodbye to Gus and settled into the cab of Lai Singh for a pleasant ride through country I was looking forward to seeing.

The drive started well. We moved fast, beeping the horn and weaving in and out of garishly-painted trucks whose horns trilled like electronic songbirds when they replied. In India, I was delighted to learn, blowing the horn isn’t an expression of anger—Indian motorists blow their horns like American pedestrians nod at one another. It’s a matter of courtesy and routine, just a way to say hello and I’m-about-to-pass-you. Delhi was a maze of trucks and rickshaws, highways and streets, grand buildings and shanties. I was excited.

And then the fog rolled in. I mean serious fog, like I’ve only seen once or twice before. We’d gotten a late start on the driver because of the difficulty in communicating with the cab company, and it was midnight when we hit the fog—or the fog hit us—with full force. According to the news reports on my iPhone, the fog was delaying not only cars, but airplanes and trains. Consider that—the fog delayed trains. It’s not like trains have great difficulty in choosing their direction of travel–that’s pretty well decided already. This was serious fog.

fog through the windshield

From midnight to 3:30am, we slowed to a crawl. We averaged 35 kmh—about 22 mph. Even then obstacles appeared from the murk with disturbing rapidity, and Lai Singh’s brakes got a workout. I also discovered, upon quick calculation, that 35 kmh is a discouraging rate of travel on a 270 km journey.

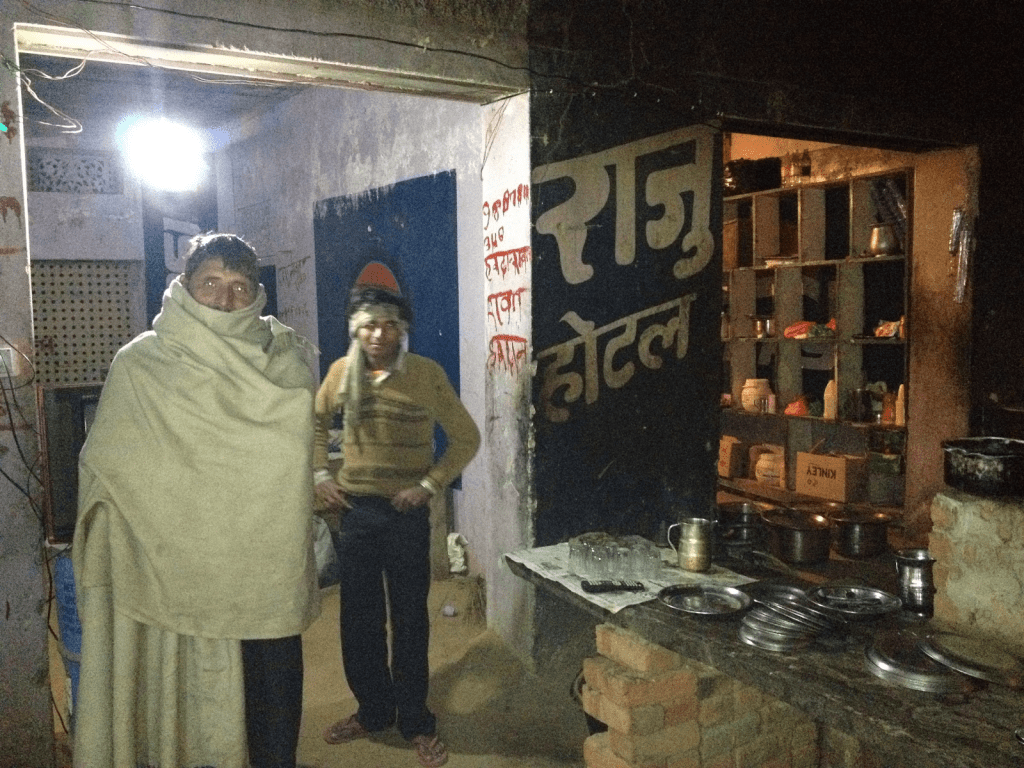

This was a long drive and hairy enough to make me nervous. My driver was frustrated, and I had difficulty feeling him out, as he spoke no English other than “okay” and “rupees.” I spoke no Hindi. I was cursing myself for exposing myself to this risk, because I was entirely at his mercy. He stopped once in the middle of the highway to converse with another cab driver in the lane next to us. He stopped again for food in a place that had shut down. He stopped to converse with another driver, and after they spoke on the side of the highway, he charged me another 200 rupees. I groused a little bit just so I wouldn’t appear to be a pushover, then paid. We stopped again for chai. Then we drove on.

stopping for chai

The fog cleared about 150 km outside of Jaipur, and at about 5:30 am, luggage in hand, I walked up the stairs of the Siddharth Palace hotel. It was a wonderfully clean and safe-feeling place. I entered the room that I was to share with my law school buddy Naveen Ramachandrappa. I woke him up and immediately gave my very drowsy-looking friend a bear hug. I have known Naveen for a long time now, and have enjoyed his company on many occasions, but I have never been quite this glad to see him.

December 24, 2012: Education in a Foreign Land

Merry Christmas! It’s about 8:00am here and we’re preparing to head back to the school/community center. I’ll share a few photos and notes from yesterday, Dec. 24, while Naveen showers.

(Ladies, please contain yourselves—the photos will not be of Naveen showering.)

We spent most of yesterday in what I’ll call an alternative school—a one-room building and rubble-strewn yard where one of our program directors, Nutan, has taught for four years. Her pupils generally aren’t in school elsewhere, and the education that Nutan and her volunteers is able to provide is very, very rough. Yesterday morning, we worked with a group of mostly 9 to 12-year-olds of both sexes, then spent the afternoon with 12 to 16-year-old girls. Generally the children speak Hindi but no English.

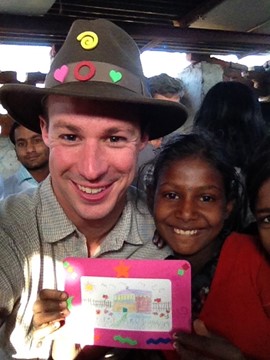

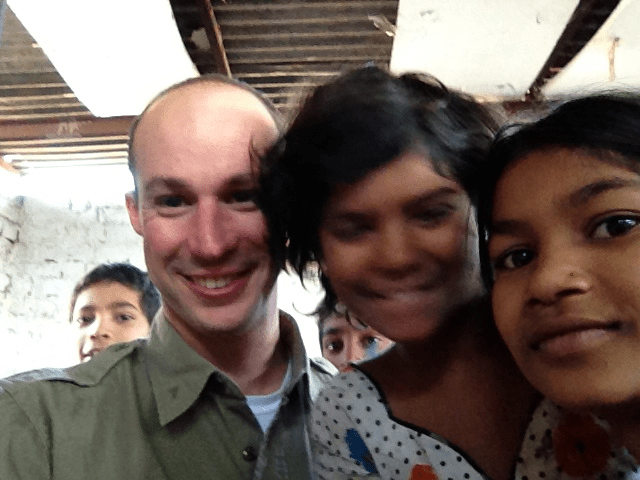

Nutan and me

inside the school

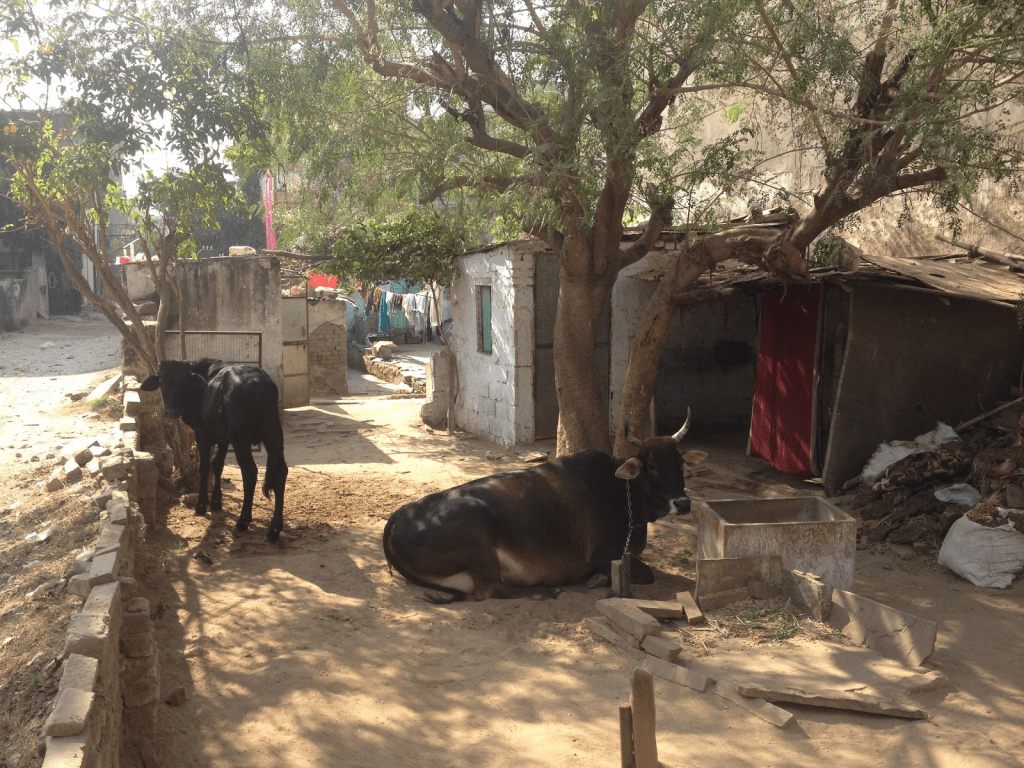

outside the school

the schoolyard

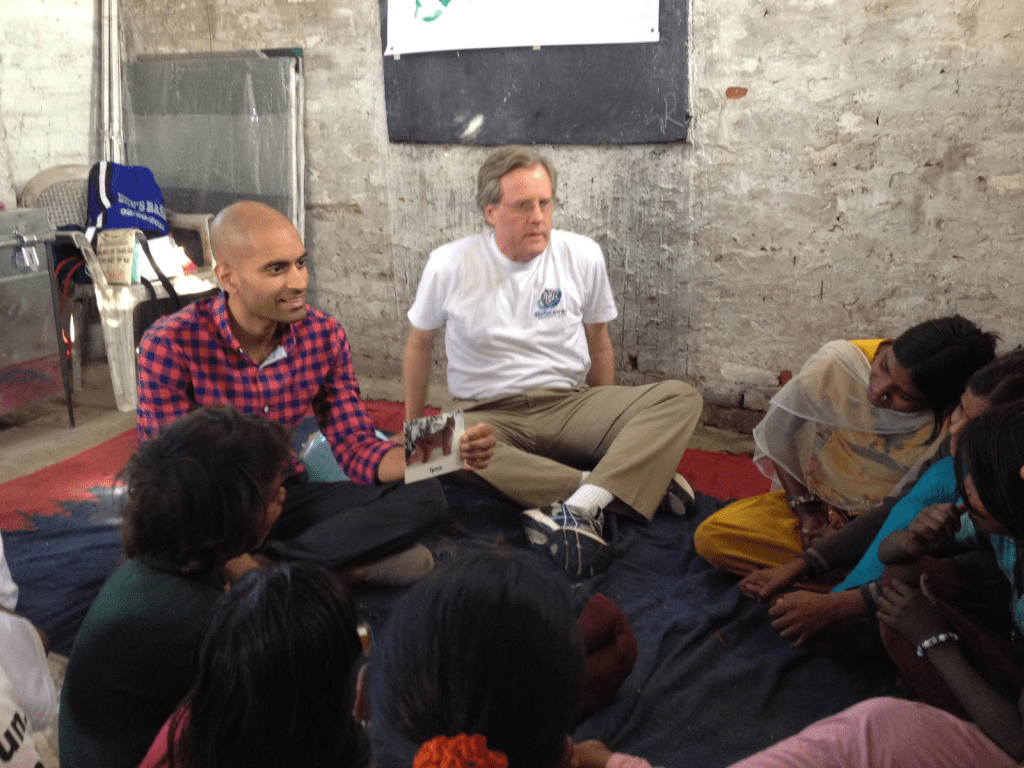

There is a family on this trip with Naveen and me that is presently participating in its sixth Globe Aware vacation. John, Meg, fifteen-year-old David, and David’s friend Nikhil brought a treasure chest of teaching tools with them, including world maps, inflatable globes, magnetic letters, and cards with animal photos and names. Those tools greatly aid our pedagogical efforts.

We began each session sitting around in a large circle with the children and introducing ourselves, giving our names and some detail with which we thought the children could identify. For instance, Naveen tells the group that his family is from around Bangalore, and I tell them that I’m from Georgia, home of Coca-Cola. The children introduce themselves and ask questions of us through Nutan and A.J., a local who works with Globe Aware. We often talk about sports—cricket is a local favorite.

We break into smaller groups and attempt to give something of a formal education, pointing out various places on the world maps and globes and teaching the children to pronounced their names. Yesterday, I taught my groups to identify Russia, India, Australia, U.S.A., and Africa. Some of them already knew where India was, but everything else appeared new to them. We reviewed the animal cards, and pointed out where giraffes, penguins, spider monkeys, etc. lived. I’d encourage the kids to point to the map as they spoke the name of a place, and give high-fives when they got something right. I also encouraged them to shout, as that is both entertaining and kept me awake, as I’d arrived at 5:30am and gotten up three hours later. Our group had a great chant of “Russia!, India! Australia! U.S.A.! Africa!” going until Nutan asked us to quiet down.

* * *

India is experiencing the paroxysms of modernity, and it is fascinating to watch. Outside the gleaming, glass-sided offices of international corporations, cattle, goats, and hogs eat garbage in the streets. Beside the speeding, beeping Tata automobiles, camels pull carts of produce to market. Women in particular are driving social change. In Delhi and Jaipur, the recent gang rape of a 23-year old woman has sparked protests seeking to overhaul India’s lenient, outdated rape laws. The protests have caught the Prime Minister’s attention. In our afternoon class, Nutan argued with a 20-year-old woman who came by about the direction that the young woman’s life could take—Nutan said there was a future outside of domestic work. The young woman wasn’t so sure. In our morning class of 9 to 12-year-olds, the girls were noticeably better students and quicker learners than the boys. The future may be theirs.

lunchtime

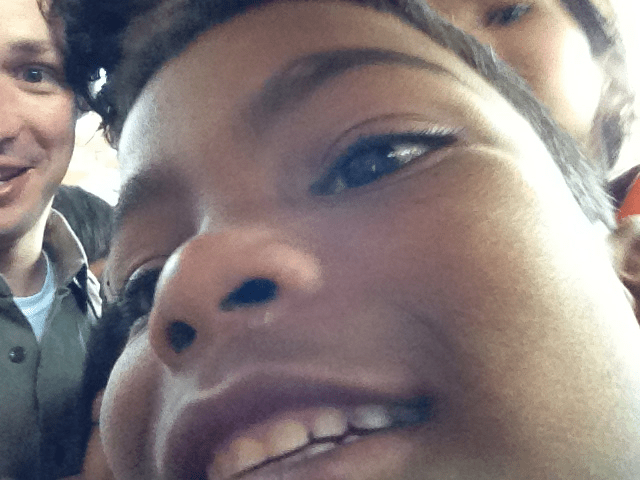

making some faces with the cameraman

splish, splash

mooooooo

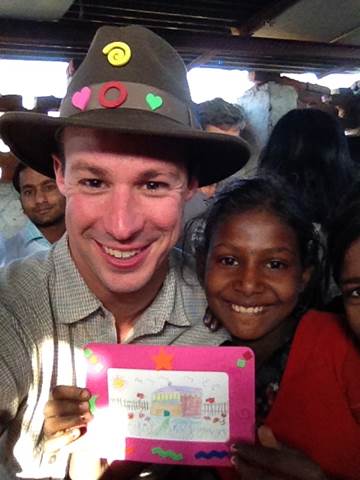

renowned international educator James E. Butler III with two bright pupils

Naveen Ramachandrappa with some goats

December 25, 2012: Enthusiastic Education

As we set up for the morning session, the younger kids scramble underfoot and put their hands on everything. “Back, back!” we have to say. They stay until we leave for lunch, then they follow us to the van. The afternoon session is for the older kids, and we have to force the young ones to stay outside. After the session the older kids hang around and help us clean up, then they follow us to the van. They run alongside the van as we are leaving and I hope they’ll stay out of the way of the tires. “Bye bye!” they scream; “tomorrow!” they insist. The kids love school. It was a wonderful way to spend Christmas.

The great thing about children, I am learning, is that they are childlike. These children bear no sense of sorrow or misfortune and therefore we, the teachers, feel no sense of pity. We couldn’t if we tried. They make it impossible to remember that this is a slum and these children lack the basic opportunities that Americans take for granted. I hesitate now to use the term I used before I left—“slum kids”—not because it is inaccurate, but because it feels inaccurate.

the kids love to have their pictures taken on my iPhone

more iPhone fun

still iPhoning

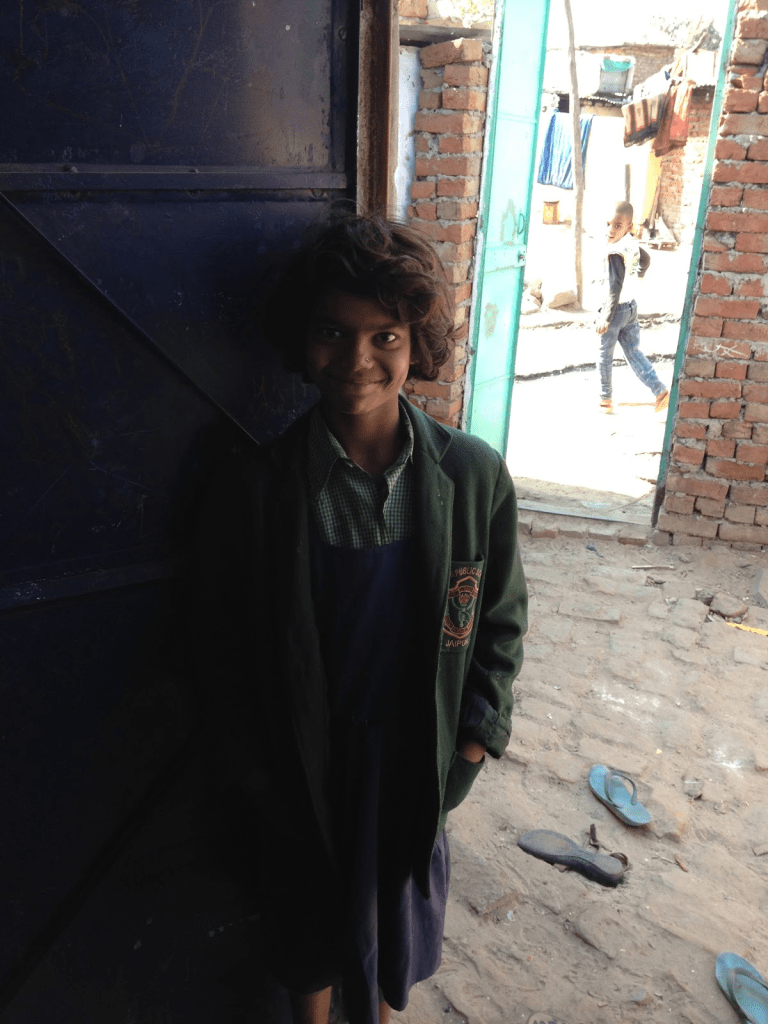

One of the girls runs toward the van as we’re leaving. Although the dust and light are not good, this is my favorite picture.

Nutan works long, long days to help these children. She encourages them to take whatever education she can give so they can move up and out of the slum when they’re older. She has taught at this classroom for five years. After teaching, she meets merchants and artisans in the marketplace in hopes of placing her students with them when the children are old enough. Nutan promises her students that if they learn, they can move outward and upward. She plans to keep that promise.

Although India is liberalizing, the society remains conservative. As I was showing pictures of Anne to the children, I asked Nutan for the word for “girlfriend,” and it was the same as for “friend”—in India, she explained, boys are not supposed to have friends who are girls, nor girls have friends who are boys. So there is no need for the word. A set of social rules governs when, and under what conditions, girls can be in the same room as boys with whom they are not related. Arranged marriages of boys and girls who do not know each other are still common. Nutan was married at 23 to a man she saw for the first time three days before the wedding. And even Nutan—who champions the liberalization of India, although wouldn’t put it that way—must rise before dawn each day to clean her house and cook for her family.

Yet the social changes are obvious. Girls and women are attending school now. Yesterday morning, an irritated mother came to pull her daughter out of our classroom so that the daughter could fulfill her domestic chores—but the daughter came back later. Yesterday afternoon, we visited a classroom of grown women learning the days of the week and months of the year in English—preparing for jobs outside the home. I have not yet seen Nutan wear the cloth with which many Indian women wrap their faces and faces. And when we asked Nutan about what would happen when her own daughter reached marriageable age, she said: “she will choose.”

India is charging enthusiastically into the future, and feel lucky to be here.

it doesn’t matter who or where you are, maracas are cool

at the classroom door

Nutan and students

December 26, 2012: Candles and iPhones

The light blue sky was patched with pink when I sat down on a low brick wall near the hotel to write. Indian music played in the distance; children laughed from around the corner. The air was cool and pleasant. A man drove by on a scooter holding a smartphone to his ear. Another dumped his trash can in the empty lot beside the wall I was sitting on, contributing to the exiting mess of plastic wrappers, disintegrating cloth, and rotting food. This, I have learned, is India.

A group of neighborhood children looked at me and I waved. Within minutes I was surrounded by a gaggle of children, aged 8 to 12. They were bold and well-spoken; their English was excellent. They gawked at my laptop and phone. They asked what games I could play on them. I asked about their schooling. Multiplication and division in math, Indian government in civics, and of course English. They liked soccer, dancing, and flying kites. We talked about “Gangam Style,” and their laughter filled the streets when I imitated Psy’s dance moves. A twelve-year-old boy—maybe the most poised twelve-year-old I’ve ever spoken to—told me about the shop where he worked and explained that he wanted to move to America because India was too corrupt. A young girl told me about her career goals. They wanted iPhones, aspired to be doctors, and mused on moving to America one day. Their clothes were clean and a few invited me into their homes.

neighborhood kids fascinated with the iPhone camera

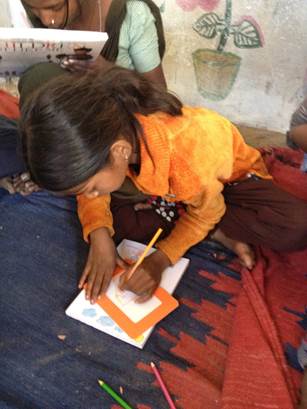

After an hour, it was getting dark and I said goodbye to the neighborhood kids. I returned to the hotel to write and remember the earlier hours spent with “my” kids. In the classroom this afternoon, we had the 12 to 16-year-old girls draw pictures inside small frames. They drew with colored pencils, then decorated the frames with stickers. Almost all of the girls drew houses. They drew flowers and one drew a water pump. After they had drawn the pictures, we sat in a circle and each girl stood to describe what she had drawn. Nutan had to translate because the girls’ English was insufficient for the description. Over and over again, these girls—who live in wall-sharing slum homes interspersed with bare dirt paths and sewage ditches—said they wanted houses. They wanted clean water and flowers outside. They wanted candles. The didn’t mean scented candles—candles so they could see at night.

The neighborhood kids wanted medical degrees and iPhones; my kids want clean water and candles. The neighborhood kids had clean clothes and internet access; my kids have at most two sets of clothing and little access to written material of any kidn. The neighborhood kids spoke excellent English; my kids have a long, long way to go.

Nutan is a devoted teacher, and we volunteers are rooting for them. But I’m having a hard time convincing myself that it’s enough.

Patima draws her picture

Nikhil, John and some students with finished pictures

Mumta with my hat

as you can see, my hat is universally considered stylish

now made even more stylish by students

one critter’s trash is another’s treasure

playing in the schoolyard

December 27, 2012: Shapes of India: issquares, isstars, and hearts

“Triangle,” I said, pointing to the shape on the blackboard with “triangle” written next to it. A disjointed murmur came back from the kids seated in rows before the board.

“Three parts,” I said, holding up three fingers.

I turned sideways to the kids with my feet together and looked at the kids. They were sitting cross-legged, eyes bright and attentive. I hopped forward about a foot. A puff of dust arose where my shoes hit. “Tri!” I shouted.

“Tri!” they shouted.

I hopped again. “An!” I shouted.

“An!” they shouted.

I hopped again. “Gle!” I shouted.

“Gle!” they shouted.

“Tri-an-gle!” I said.

“Tri-an-gle!” they said.

I pointed at half the room. “Tri!” I said.

“Tri!” they responded.

“Tri!” I pointed to the other half.

“Tri!” they responded.

“An!” I said to the first half.

“An!” they responded.

“An!” I said to the second half.

“An!” they responded.

“Gle!” I said to the first half.

“Gle” they responded.

“Gle!” I said to the second half.

“Gle!” they responded.

“Tri-an-gle!” I shouted to all.

“Tri-an-gle!” they said.

I held my arms out to my sides and belted it out: “TRIANGLE!!!!!!!!!”

“TRIANGLE!!!!!!!!!” they yelled.

“TRIANGLE!!!!!!!!!” I yelled.

“TRIANGLE!!!!!!!!!” they yelled.

I crouched in front of a quiet girl and held my face close to hers. I smiled. “Triangle,” I whispered. The kids giggled. “Triangle,” she whispered back.

And on it went, with squares, circles, diamonds, rectangles, ovals, stars, and hearts. Then we’d review, as I pointed to a shape and hoped the kids remembered its name. Some did, and some didn’t. We’d practice again, and review again. Diamonds and hearts were the kids’ favorites. They had a hard time with ovals. They struggled to pronounce “square” and “star”—they instinctively added an initial “i” to the words, pronouncing “issquare” and “isstar.” John, Nutan, and I all tried to straighten this out but with limited success. Maybe there are no Hindi words beginning with “s.” Eventually we moved on—we had a lot of ground to cover and not enough time to chase perfection.

School has to be fun because the kids don’t have to come. According to my understanding, India has regular school system in which attendance is compulsory (though our school is not a part of it), but these kids are left out of it. Although Indian law technically requires their attendance at an official school, as a practical matter, the law doesn’t reach these kids. There are three reasons. First, they live in the slum, and officials are simply less concerned with the attendance of these kids. Second, these children’s parents often require that they stay home to assist with domestic tasks like cleaning or caring for younger siblings. Third, these children’s parents—whether because of social conditioning or their personal values—sometimes do not emphasize education.

I can’t help but suspect that the vestiges of the caste system contribute to this. The caste system has been officially abolished, but I have a hard time believing that the social mechanisms that underpinned it disappeared as quickly as its legal recognition. In the American South, for instance, the social underpinnings of slavery—i.e., assigning blacks a status lower than that of whites—persisted long after the legal recognition of slavery had ended. So it must be with the caste system—social discrimination persists after legal abolition. The lower social status of the adults who live in slums may cause officials to care less about the future of slum children, and may contribute to slum parents’ conclusion that attaining an education would be pointless. And so, when all is said and done, if our kids decide not to come to school, then nobody will make them.

After we finished with shapes, Meg passed out pieces of cardboard with frames as we’d done with the older children the day before. They had liked this exercise. First we distributed crayons for drawing pictures, and many of the same themes emerged today as yesterday—houses, flowers, and light sources. Then Meg distributed stickers of various shapes and colors to decorate the frames. I sat down in a circle of children to help with the stickers.

One girl sifted through the pile of stickers until she found a shape she liked. She looked at it as she held it in her hand, and after a moment she showed it to me. “Heart,” she said.

That’s what I was hoping for.

working on a picture frame

more framework

Meg showing the kids some pictures she took

completed pictures and frames

smiling kids

December 28, 2012: Reminisces of the Pocketman

I’m seated now in the first-class car of an outbound train, the sun is rising over dew-soaked fields, the tea they serve is hot and good, but I can’t forget these kids and I hope I never do.

Patima, with her big-buttoned orange coat; smart and serious-minded; quiet; respected by her peers younger and older. Norti; scar on her cheek; irrepressibly bold and charming; unconscious leader; occasional troublemaker; ambivalent about academics. Mamta; dirty white dress coming unstitched at the seams; smart and assertive, charismatic, but troubled, moody, high-maintenance, family hostile to education. And the rest, some of whose names I know and others whose I never learned.

Patima, middle

Norti

Mamta, left

And Nutan. One of my favorite people I’ve ever met. Up at 5:00 every morning to clean and prepare meals for her family and two American students for whom she’s serving as a host family. Picks the volunteers up every morning in her sari and faux-leather jacket. Answers our questions on the way to the slum, then teaches with us until lunch. Lunch with us; answers more of our questions; teaches with us in the afternoon. Sometimes dinner with us. Home to care for her daughter and prepare more meals for her household. Between it all, makes contacts at the bazaar so her students can have better access to the job market. She does this without realizing how extraordinary she is. What makes Nutan unique is that she neither appreciates herself nor has any need to appreciate herself. When I called Nutan “Superwoman” she liked the compliment, but neither expected nor needed it.

Nutan and me

She paid me a compliment I will not soon forget. “I have learn from you,” she said. “You are a good teacher. All-time-smile.”

The children gave me much to smile about. They were so excited to attend school, and against the background of the slum their smiles shone like stars against the night sky. Many of them called me by a name Nutan gave me—“Pocket,” because the Hindi word for pocket is either “jeb” or “jev,” I forget which. So on the last day, when we took the young kids to the park, the park was filled with high-pitched calls for “Pocket!” or “Pocketman!” as kids with inflatable balls wanted to throw them with me, kids on swings wanted me to push them, and kids on the slide wanted me to watch. They did not know, and will never know, what a gift they gave me by making me a part of that joy.

The farms and fields out the window are soothing and beautiful. But I will forget them long before I forget the faces and feelings of my city kids.

swinging

David hoists a young ‘un

goats and men of a nearby slum

Jaipur train station

cup of coffee and view from the train

a particularly handsome traveler

water buffalo walking among patties of their excrement, gathered and shaped by hand then left in the sun to dry for use in cooking fires

December 29, 2012: Raw

It’s actually the morning of the 30th, and I’m sitting on the patio of my hotel sipping a Kingfisher and wondering how to best to sum up India, or at least Rajasthan, the state where I’ve spent most of my time. Several phrases come to mind. Fascinating mixture of the ancient and modern. The great unwashed. Thatched-hut agriculture meets bustling urbanity. Crowded and dirty. International-jet access to exotic biota. Heedless environmental destruction.

Of course you can’t encapsulate India or Rajasthan in one phrase, but the best summary I can think of—at least when comparing this place to my home in the United States—is raw. That’s both a good thing and a bad one.

Raw is the incredible biodiversity of Kheolado Ghana National Park, where I went walking yesterday and running this morning—it has received recognition from UNESCO and other international organizations, and I can’t think of anything like it back home in Georgia. Raw is the give-and-take bargaining over bananas, samosas, and chai on the street, a local market exciting in its efficiency. Raw is new Tata trucks beeping their horns as they swerve over the centerline to pass camel-drawn wagons. Raw is exciting.

But raw is also the sordid water, soap swirling alongside sewage, running down the dirt paths that connect the homes of my students. Raw is the garbage that clutters the vacant lots and railways, deposited by masses for whom a wastebasket is a foreign concept. Raw is a water buffalo, kept so that its milk can be drunk and its feces used for cooking fires, tethered so close to the ground that it cannot stand and raise its head at the same time. Raw is brutal.

I don’t know why I travel for answers; observation and objectivity always create more questions than resolutions. In about a day, Anne and I will travel from Atlanta to Savannah to celebrate the new year with friends. We will spend a couple hundred dollars on travel, lodging, food, and drink. In this raw country, that money would go far. If Anne and I stayed home and sent that money to Nutan, she could buy benches for the classroom, books for the shelves, lunches for the children, and then some. (I have already left some money for these things, but more could be better.) Is it ethical for me to travel to Savannah to drink high-priced beer on River Street?

This raw world is full of uncomfortable questions.

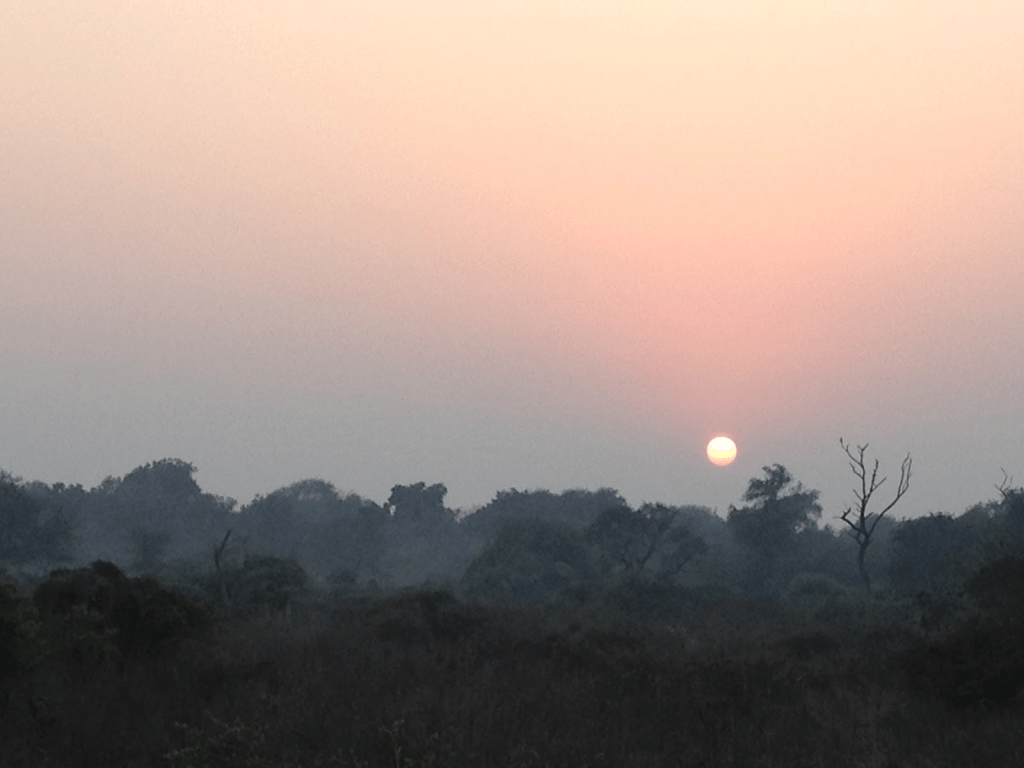

After the cacophonous city, I was looking in Kheolado Ghana National Park for some nature-based tranquility. I found it off the trail in this spot.

sunset in Kheolado Ghana National Park

I went for a run in the morning fog of Kheolado Ghana and ran right through this tribe of Macaque monkeys.

Waterfowl in Kheolado Ghana National Park. The fog was beginning to lift.

Street food. I told the vendor I wanted it spicy, pointed to my chest, and said “Rajasthani man!” It was hot, but very good.

December 30, 2012: On Volunteer Vacations

As Nutan concluded class on our last day, I leaned against the back wall and checked once more that Mamta was present. I wanted to make sure she got a copy of the “School Book.” She was there, sitting in her smudged white dress, paying strict attention to the teacher for once.

The School Book wasn’t much. It contained numbers, written in Arabic numerals alongside their Hindi and Rajasthani spellings; tables for addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division; the months of the year, the days of the week; a map of the world; and a map of India. I created it on my laptop early one morning, asked the other volunteers to contribute to it over breakfast, then had the hotel print copies while we were out teaching. It would be, as best I could tell, the only schoolbook these children had.

The forty copies I’d asked for weren’t going to be enough. We’d distributed twenty-one copies to the older kids the day before, but Mamta—who was old enough for those older-kids’ sessions, but still young enough for this younger-kid session—hadn’t been there. Now, as I counted the heads seated on the dusty blanket spread across the floor, I saw we’d be five or six copies short. No matter—some of these children were too small to read anyway.

Nutan started to conclude and the kids started to move around. As Mamta turned to stand I tapped her on the shoulder. “Wait,” I whispered, holding my palm out to her. “One minute. I have something to give you.” Her face was a question. I gestured as if passing a gift to her, then motioned again for her to sit. When Nutan finished, I moved toward the aluminum chest that held the remaining School Books and gestured for Mamta to follow.

Nutan knows that Mamta is one of my favorites. Mamta’s face is expressive but matter-of-fact—she can warm your heart with a smile or instill guilt with a scowl. She’s smart, assertive, and charismatic. She is also mercurial. Sometimes she needs discipline, as when we were playing “music” in a small circle and Mamta kept taking other kids’ instruments. I warned her twice, provoking eye rolls, then confiscated her instrument, provoking a scowl and some nasty-sounding Hindi. I leaned forward, mimicked her scowl, laughed to show gentle mockery, and kept the instrument. That appears to have been the right move, as Mamta and I were friends after that. Mamta would approach me before class to hold hands or slap high-fives, and I liked it when she did. In retrospect I think Mamta wanted affection but didn’t know how to ask for it.

I opened the aluminum chest and pulled out the stack of nineteen School Books. Nutan, who noticed what I was doing, explained in Hindi to Mamta what the School Book was and that I wanted her, in particular, to have one. I turned, stack in hand, and gave a copy to Mamta. Her expression was uncertain as she figured out what this was.

You cannot hand an item to one child in a classroom without every other child in the room rushing forward for the same thing, and I was immediately surrounded. Little children with little open hands, reaching, jumping, chirping “sir!,” “sir!,” “sir!” (This is especially true if some of the children have experience as street beggars.) I held the stack high so the children could not reach them, and moved across the room so I could set it down on a high wall and use both hands for distribution and crowd control. Kids who had no idea what the School Book was and would not have cared about it if they had known desperately wanted a copy. I distributed to the older children first, then to the younger ones, trying to place each copy in the correct hands without another hand grabbing it first, trying to ensure that siblings had a copy to share, trying to ensure that larger children didn’t come back for a second copy before the smaller children got one. In the midst of it all I saw Mampta pushing into the crowd, reaching. I was not going to give her a copy because she already had one, but she was reaching for my empty hand. As I turned toward another kid to hand out a book, I heard her say “thank you” and I saw her face—an appreciative expression—out of the corner of my eye. I kept distributing the school books, figuring that I’d have that conversation with Mamta in a few seconds when I was finished.

* * *

Intimacy does not come easy, but it is worth chasing. If the point of traveling is to experience and learn about something new—as opposed to merely doing the same things in front of a new backdrop, or snapping photos of Wikipedia-ed landmarks so you can prove that you’ve been there—then intimacy is irreplaceable. If yours is a people-oriented trip, it is not enough to see them in restaurants, hotels, and the street. You’ve got to participate in their daily lives. If yours is a nature-oriented trip, it is not enough to see the terrain from a train window. You have to shoulder a pack and live in it. Those are not easy things to do.

At intimacy, volunteer vacations excel. Had I come to India without GlobeAware (my volunteer vacation company), I would never have met any of the children. I would not have entered a slum. I would not have gotten to know Nutan. I would not have experienced the closeness of the slum, the smell of the people, the sounds of an upstairs neighbor walking across the sheet of tin that constitutes the ceiling. With GlobeAware, I could join the camaraderie of the children, feel their small hands in mine, hear the happy shouts of “tri-an-gle!” as I hopped across a dusty floor. I could ask Nutan frank questions about her arranged marriage and I could feel the way that India is changing.

* * *

As soon as I handed out the last School Book I looked for Mamta. She was gone from where the circle of kids had stood and gone from the schoolhouse. I stepped into the schoolyard, but I did not see her. I stepped through the metal door into the dirt paths of the slum, scanning for the hip-height girl in the smudged white dress. She was not there. I wanted this last goodbye with Mamta; I wanted her to know that she was special to me; I wanted to know that I meant something to her. I left the group and walked to her house. Nothing.

I never found her. Since then I have often remembered her, and Nutan, and the other children, and I regret that my last interaction with Mamta brought no more closure. I wish I had not turned away when she came to say thank you; I wish I had not ignored her outstretched hand.

Fulfillment is meeting an outstretched hand. I hope that one day, Mamta can read this post. But I am thankful that, through this volunteer vacation, we were at least able to brush fingers.