This page is for people who may fly with me, such as family members, friends, coworkers, or Angel Flight patients.

About the Airplane

I own and fly a 2019 Cirrus SR22, a five-passenger propellor-driven airplane. The airplane cruises at about 160 knots, which is about 185 miles per hour. I typically cruise between 5,000 and 12,000 feet in altitude. The airplane has air conditioning, heat, and wireless internet. It is a modern, capable, safe airplane.

The plane is equipped with a whole-plane parachute. In the center of the ceiling, in reach of all passengers, is a red handle. If you pull it down, a parachute will come out of the back of the plane. The entire plane, including all occupants, will descend to the ground. The parachute can be used by the pilot if something goes wrong with the airplane or by a passenger if the pilot becomes incapacitated. Landing under the parachute will not be pleasant but if the parachute is deployed correctly, the landing will be survivable. Here is a two-page safety card that describes its use.

The video below shows an early test of the parachute system by Cirrus. In this test, the pilot deliberately put the plane into a spin, then pulled the red handle.

The airplane is also equipped with an anti-icing system designed to prevent ice from forming on the airplane if moisture is encountered in sub-freezing temperatures during flight. The anti-ice system uses a deicing liquid called TKS fluid. When a switch is flipped in the cockpit, TKS fluid flows through tiny openings in the leading edges of the wings and tail structures, and also onto the prop. Another switch heats certain external instruments to prevent them from freezing. I use the airplane’s anti-icing system only as a failsafe mechanism. We will not deliberately fly where significant ice is observed or predicted.

What to Expect

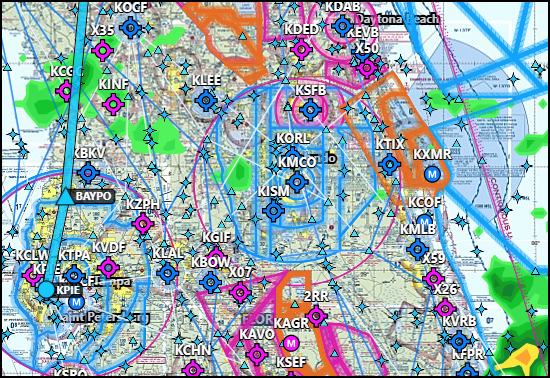

Every flight starts with weather planning. I use commercial weather predictions and aviation-specific weather analyses available through ForeFlight, the Aviation Weather Center, and Windy. I do not fly in or near thunderstorms or significant icing conditions. We can safely fly through clouds or moderate precipitation.

If conditions are not safe, we will not fly – period. Typically, I can get a feel for likely weather conditions two or three days before a planned flight. Depending on conditions, we may not know for sure whether a flight can be made until the day of departure. For that reason, I sometimes ask passengers to buy refundable commercial airline tickets in case conditions are not good, because commercial jets can often fly in weather that I avoid.

Before we get in the plane, I will preform a preflight check. This includes testing the airplane’s electrical systems, walking around the plane to see and feel inspect the control surfaces and other external structures, sumping the fuel tanks to inspect the quantity and quality of the fuel, and checking the engine oil. If you are meeting me at the airport, I may arrive early and perform the preflight inspection before you get there.

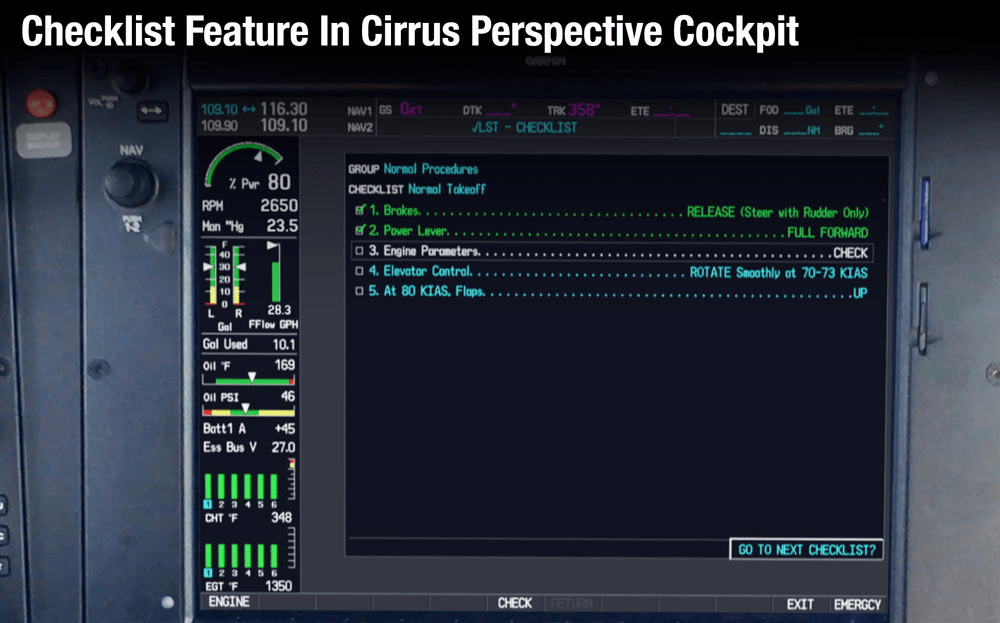

After we get in the plane and start the engine, we will sit still for a minute or two. During this time I will typically check the radio report of the weather at the airport, enter our flight plan into the avionics, and talk with either the control tower or other pilots on a common frequency. I will use a checklist of to-do items that appears on the right screen in the cockpit.

We will then taxi the plane to the end of the runway or the “runup pad,” depending on the layout of the airport. Then, unless I have just flown the airplane, I will perform a series of additional checks. Those checks include setting the avionics, testing the autopilot, rechecking the control surfaces, revving up the engine and observing the temperatures in each cylinder and each exhaust stack, and setting the flaps. As with most phases of flight, I will use a checklist that appears on the right screen.

During takeoff and climbout, I ask my passengers to keep quiet so that I can focus on flying. During the takeoff roll, I’ll check to make sure that the airspeed indicator is working and that all instruments remain “in the green.” Depending on the weight of the aircraft, we will take flight when we reach 71-73 knots. We will then climb out at a predetermined airspeed until we reach either our cruising altitude or the altitude given to me by air traffic control (“ATC”).

“Cruise” is the long part of the flight where we sit back and let the autopilot take us where we’re going. If the weather is clear, then we can fly under “visual flight rules” and I don’t have to talk with ATC – we need only monitor traffic visually and with our on-screen detection systems. If the weather isn’t clear, then we must fly under “instrument flight rules” and I will have to remain on the radio with ATC and other pilots during the cruise portion of the flight.

Cruise is also the phase of flight in which passengers can talk freely, look out the window, or use the wireless internet. Feel free to ask me about the airplane or what we are doing – I love talking about flying. Passengers are welcome to eat or drink but not smoke.

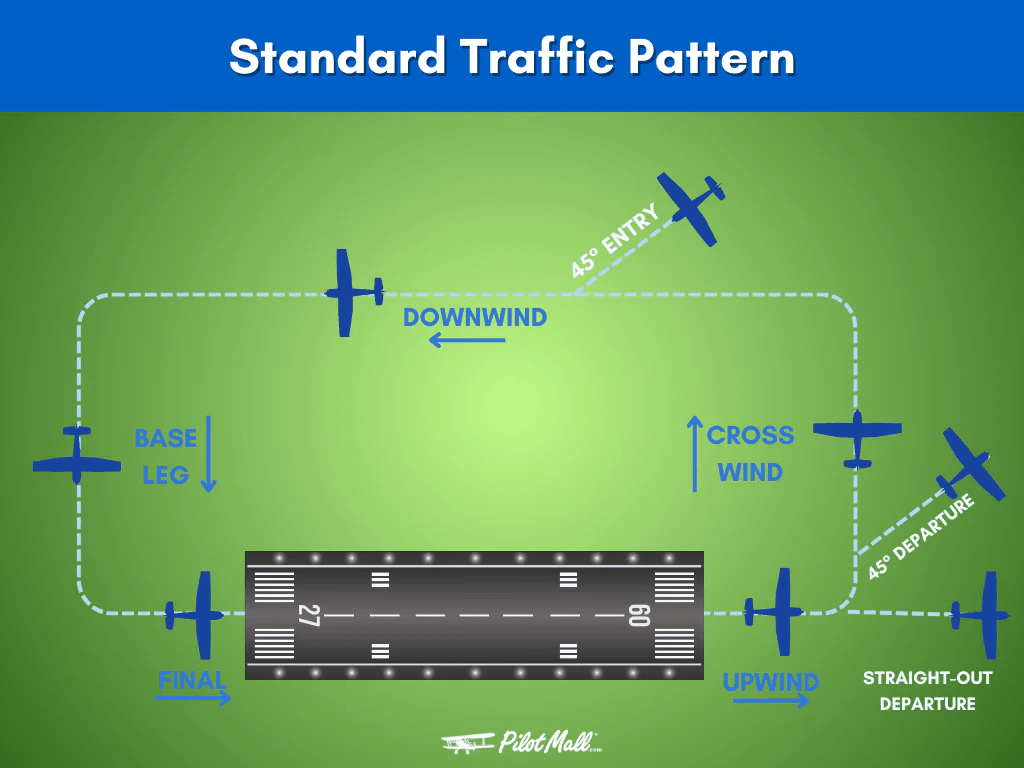

During the descent and landing phases, I ask my passengers to keep quiet or at least not talk to me. As we near our destination, I will check the weather broadcast over the radio for that specific airport and begin maneuvering to land on our chosen runway. Sometimes we will line up and come straight in to our chosen runway, and sometimes we will get near the runway and make a few standardized turns – usually called the “pattern” – to get lined up. If our destination airport has a tower or if I’m flying under the direction of ATC, then I will be following instructions. If there is no tower and the weather is clear, then I’ll set up for landing myself and communicate with any other pilots on a radio frequency specified for that airport. Again I’ll use on-screen checklists.

During the landing phase, I will focus only on flying and will not talk with passengers. As with most aircraft, we land with the two main (i.e., rear) wheels first, then let the nosewheel touch down. If there is a crosswind, then it will appear that we’re at an angle as we approach the runway – we will be flying directly toward the runway, but the nose of the airplane will be pointed slightly off-center on the upwind side. As we near the runway and get within 200 feet of the ground, I’ll straighten the airplane and dip the upwind wing slightly. That will keep the fuselage aligned with the runway and the airplane moving in the right direction. We will then land with the upwind main wheel first, the downwind main wheel second, and the nosewheel third.

We will then taxi to our destination on the destination airport. I will then shut down the airplane, again using an on-screen checklist.

Turbulence can be uncomfortable but is not dangerous. We are most likely to encounter turbulence during climbout or as we descend to our destination. The majority of the flight is typically smooth because I can usually find a smooth altitude to cruise at. Turbulence is most common on summer days (because the heating earth causes air to rise at uneven rates) and when we are climbing or descending near the base of a cloud layer.

About the Pilot

I started flying in 2009. For years I owned and flew a 1977 Cessna 182, a four-seat propellor driven airplane. In early 2017, shortly after my first child was born, I stopped flying and sold the plane because between my family life and professional obligations, I did not have time to keep proficient. In 2022, I started flying again. I earned my instrument rating, which means that I got qualified to fly when the weather is not ideal and through conditions where you can’t see well. After that, I transitioned to Cirrus aircraft with Aero Atlanta Flight Center, which operates one of the largest Cirrus rental fleets in the world.

I bought my current airplane in February of 2024. I’ve flown thirty-five different airplanes and have over 900 flight hours, and now have more time in Cirrus than anything else. The longest trip I’ve taken was from Phoenix, Arizona to Atlanta, and the longest single leg I’ve flown was from Atlanta to North Eleuthra Airport in the Bahamas. I fly on family vacations, on Angel Flights, for fun and practice, and whenever else I can find an excuse.